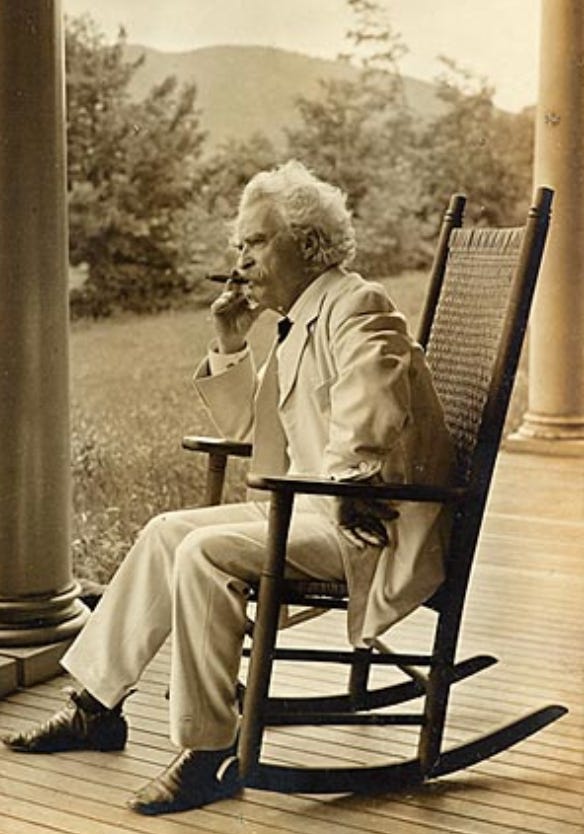

Samuel Clemens; Monroe County Native (born not far from where my mother grew up)

& Fellow Hannibal Educated Writer. Photo Used Courtesy of Morgan Library & Museum

Sometimes a thing makes so much sense… as soon as I read it I wonder how I didn’t know it all along?

Author Gregory Crouch, in a snippet from his biography of 19th Century mining multi-millionaire, John Mackay, entitled Bonanza King, ascertains that Mackay’s close and personal friend, Sam Clemens, didn’t really take his world famous pen-name from his riverboat days upon the Mississippi River, but from Sam’s rough and tumble drinking days in the saloons of Virginia City, Nevada Territory, in the early 1860’s. How young Sam ended up out west from his days as a steamboat pilot is a true American Odyssey that couldn’t have taken place anywhere else at any other time. Like Odysseus himself, Sam weren’t a fool, and the story of how he went from being a riverboat pilot, to Confederate bushwhacker, to gold miner, and eventually creative writer/ author is a trace in pragmatism that leads to the name we all know, and love, so well.

Sam was born and raised in a time and place where slavery, racism, and violence– both casual and horrific —towards Africans, slaves and free, and ‘abolitionists Yankees’ was not only tolerated, but seen as a necessity of southern pride and honor. Those southern sympathies were undoubtedly deepened by the company Sam kept as a steamboatman on the Lower Mississippi before the Civil War; the transportation industry was populated predominantly with men and organizations with deep ties and reliance on the south’s agricultural trade and the institution of human bondage. And when the war began, one of the key projects of the US Army Corps of Engineers was to disrupt traffic and commerce that used slave labor for the length and breadth of the Lower Mississippi, taking away hundreds of dollars in monthly income from Sam, which more than likely pissed him off a bit more towards those damned Yankees.

So, twenty-six year old Sam returns to Hannibal and joins up with the Confederate irregular mounted Ralls County Rangers so he could show them ‘damn Yankee so and so’s what was what.’ Problem was that the ‘Little Dixie’ loving area north of the Missouri River and south of the mouth of the Des Moines got wrapped up tighter than bark on a beech tree; Union troops embarking out of Keokuk Iowa, Quincy and Springfield Illinois, and St. Louis’s Jefferson Barracks, trapped and separated any and all southern sympathizing militias in between. With two military prospects as possibilities— being drafted by the Union through the State of Missouri, or riding south to find a Confederate regular army unit — the outlook for a military career in Sam’s mind must have seemed dismal.

Back during his days as a printer’s devil, he had traveled north and east, all the way to New York City through Ohio, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and New Jersey; he knew well the industrial might of the Union, seeing it first hand, and was keenly aware of the “Sir Walter Scott” chivalrous, backwards thinking of the Southern elites who were dependant on poor whites to fight their war. More sparsely populated, less industrial might, and a fighting force that had to be lured into fighting a war with institutional racism and a false sense of patriotism, the South had picked a fight with a foe they couldn’t beat on their own.

Certainly Sam had doubts regarding the Confederacy’s chances once he had seen the rapidity in planning by the Corps of Engineers in trammeling the Big River, and the organization of the Union volunteers and standing troops of John C. Frémont’s Department of the West, which early on in the war had much more success than the Army of the Potomac in the east; Missouri was locked down in a matter of just a few weeks, denying any chance that it might have had to join the Confederacy.

It was a no brainer; despite his southern leanings, like many young men in his posisition, he may not have been certain the Confederacy was doomed before the war had started, but that was the way to bet.

Sam’s older brother Orion, who was ironically a Free Soil supporter of Abraham Lincoln and Republican politics in general, had been appointed as a secretary to the Territorial Governor of Nevada in Carson City, and as stated before, Sam wasn’t a fool, (even if he sometimes made mildly foolish decisions) and seeing the handwriting on the wall, he knew it was time to go visit brother Orion.

A professor of mine from the 20th Century, Virgil Albertini — a devoted Twain Scholar who taught me to appreciate the Scribe of Steamboatmen, said that it was the trip west that turned Sam Clemens away from his inherited southern prejudices and moved him toward an admiration of the goals of President Lincoln and the Union. Sam even became great friends with President Ulysses S Grant post Civil War, helping the 18th President write his autobiography. Dr. Albertini also postulated that the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, published less than 20 years after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse— despite all of it’s patronizing and culturally insensitive characterizations as rightfully seen in the light of 21st Century morality —was Sam’s plea of forgiveness for his mistakes, misdeeds, and inherited hate within his youthful heart. But that was twenty years in the future of his leaving the Confederate cause; there was time for thought and contemplation ahead. As of late summer 1861, young Sam Clemens just wanted to get the hell out of Missoura and leave the war in his wake.

And Sam was not the only one; as both armies began drafting young men to fill the ranks of the fallen, thousands headed across the plains and over the Rockies into the Nevada Territory where they could not be found, at the same time Nevade was experiencing a “Silver Rush” with the discovery of the Comstock Lode beneath booming Virginia City, the territory’s largest town. For the first short while he was in the territories, Sam leapt around like a bullfrog trying to find a way to get ahold of some of the Comstock’s promised wealth, but like Tom Sawyer put to the task of painting a fence, he found the work of a pick and pan miner to be of arduous long days and dashed hopes, writing that it “was the damndest country for disappointments the world ever saw.”

Providence had other plans for young Sam other than becoming rich; always a great spinner of yarns, he began to publish some comical and bawdy sketches in Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise newspaper, using the pen name “Josh,” a metaphorical noun as a verb meaning to ‘joke’ or ‘pull one’s leg.’ By summer of 1862, while he was still digging and scratching through the gravel, Sam was submitting stories to newspapers all over Nevada and border mining communities in California. But the publisher of the Enterprise, Joseph T. Goodman, recognized talent right away, offered Sam an exclusive salary for “Josh’s” writings at $25 a week, which would be almost $780.00 in today’s money, a good salary by any means at the time. And as I said before, Sam weren’t no fool; he gave up on his dreams of being a mining tycoon, and thankfully —for our enjoyment and fulfillment– was set on his way as a man of letters.

His writing at first was raw; he had the natural emerging talents of a storyteller– embellishment, hyperbole, satire, caricature, parody, mock-flattery, ridicule, self deprecation –but with time his voice matured into something new, something entirely American, something that wasn’t trying to be English, or French or anything European or even copying of Early American literature. It grew stronger, mightier, purer, as the years took him along, like a river of time taking him downstream; his writing wasn’t like anything that had ever been penned before.

Am I a fanboy? Well, at eighteen, when I drove away, across the Ralls County Line and away from Hannibal, Saverton, and everything I knew, I didn’t give a rat’s ass if I ever heard the name Mark Twain again. Then, three years later, on the first day of my first class at Northwest Missouri State– with the aforementioned Dr. Virgil Albertini, American Lit II 1865-Present– he had us fill out cards asking: where we were from, something interesting about ourselves, stuff that professors probably couldn’t ask today, then he went around the room, calling out students and reading their card, and he came to me:

“Allen Tate-man”

“Tat-man” I corrected.

“Oh, sorry. Tatman.”

He looked at me smiling. I was a bit of a rough looking character when I first started college at NWMSU in the winter of 1983 (not that I am much better now); scraggly beard, hair usually disheveled, crooked nose, a chipped tooth or two, I always wore cowboy boots and hat, usually my old Stetson or Resistol stockman’s, and it was January so I was wearing flannel, and probably a turtleneck undershirt, and well worn Levis, all of it accented with a large German silver belt buckle with a Tiger’s Eye agate stone.

And you should also know, I was not as outgoing then as I am now. Not by a long-shot. My acquaintances met since 1988 have a difficult time believing this, but I swear it true. I was a nerd, a dork, embarrassed, trying to mask it all with denim, leather, and Copenhagen.

Dr. Albertini kept looking at me with a smile, and it started to make me nervous.

“You have the look of a real cowboy,” he said. The class chuckled. I had heard that plenty of times, had heard it from a number of assholes in Texas, mostly Texas Tech fratboys at Coldwater Country (an urban cowboy night club) in Lubbock, and I knew how to respond.

“Horseman,” I corrected. “My family, we keep horses. I’ve never driven cattle.”

“Oh, my mistake.” He looked at the card. “From Saverton, Missouri?”

He pronounced it with the short ‘a’ sound: ‘Sǎv-ur-ton.’

“Sāverton,” I corrected, with the long ‘a’ pronunciation.

“Sorry, again. I’ve never heard of Saverton before, where is it?”

“Ralls County. A little village on the Mississippi River.”

“Oh, the Mississippi! You grew up there? On the river?”

“Yessir.”

“And whereabouts on the river?”

“Just downstream from Hannibal… about eight miles.”

Dr. Albertini’s eyes lit up, a broad smile across his face, he moved closer toward me.

“So you know Hannibal well?”

“Yeah… pretty well. I went to school there.”

“Great!” he declared, “You’ll be our go to expert right off the bat! We’re going to begin with Huckleberry Finn!

How fucking wonderful, I thought. At that point I had not read any Twain in probably six or seven years, since I was a freshman or sophomore in High School and now he’s going to call me out, and I am going to look like a fucking idiot in front of these people that I don’t even know yet. Then he looked at the card again;

“OH, AND you worked as a deckhand on the towboats? On the Mississippi River? How about that?”

Yeah. Seven fucking hells. When asked about “Something interesting that you have done?” why didn’t I say, “Played baseball and delivered pizzas in Lubbock, Texas?”

But, my anxiety was relieved the next class when I realized that Dr. Albertini wasn’t going to quiz me about the literature; he asked me questions about the town that he loved so much, the landmarks, the boyhood home, Tom Sawyer Days, eventually it came up that he had been to Saverton when he and his wife had driven down to the dam to see the river and those very certain hills on the right bank I had grown to love and missed when I was away from them. And he taught me something that the English teachers in Hannibal couldn’t, because they didn’t know how to reach within me–

He taught me how to love Twain as a kindred spirit and human being, rather than just a false idol to be worshiped.

So, I would say I’m more of a brethren from rural Missoura with Sam than a fanboy. He’s been with me all the ways and days ever since.

But, I’ve drifted away from my story, as I am oft to do. So let me get this boat back on course

Sam said of his writing for the Territorial Enterprise, “They pay me six dollars a day, and I make fifty cents profit by only doing three dollars worth of work.” He found that the half day’s work schedule fit his day drinking lifestyle. He was well known about Virginia City by his real name when the legendary pseudonym Mark Twain took over his byline in February of 1863. It wasn’t until a decade later, when he started to achieve some national notoriety that he began to tell the oft repeated story that he took the name from the calling out of the deckhands announcing how many fathoms of water were ‘marked’ for a boat to safely make passage through the channel; two fathoms, or ‘TWAIN!’ it was called– twelve feet – meant safe passage for a riverboat then, which typically had about a six foot draught, perhaps a bit more, nearly the same as today’s barges.

But, according to biographer Crouch, Sam’s good friend, drinking buddy, and mining company superintendent, John Mackay, claimed that America’s most famous pen name came from an entirely different source.

Mackay often told a very plausible story that even before he started using the name in print, Sam acquired the nickname ‘Mark Twain’ in their favorite watering hole, The Old Corner Saloon. Sam would saunter in and call out “Mark Twain!” referring to a double pour of whiskey, which the barkeep would tally with two slash marks of white chalk under Clemens’s tab on the wall behind the bar.

Why Sam never told this story himself, one can only speculate, but I’m fairly certain that Mackey’s version is the most accurate. Clemans was trying to cultivate an image as a rising literary star and getting his works into the bookshops and homes of a more staid Victorian Era America back east, where he was trying to ingratiate himself. To be seen as a rustic steamboat pilot from the romanticized banks of the Mississippi was one thing; to be thought of as a heavy drinking, ill mannered westerner who frequented saloons on a daily basis wouldn’t have carried the same cachet with the salons and parlors of New York and New England.

But, that wasn’t the primary reason Sam turned away from the Virginia City drinking story…

While on the cruise back from the Holy Lands in 1867 aboard the ship Quaker City, (the trip which led to the publication of Innocents Abroad), Clemens met Charles Langdon, the son of a prosperous coal merchant from Elmira, New York. But the Langdon’s were not only wealthy, they were principled. Charles’ father, Jervis Langdon had built his business up during the Civil War, but before that had also been a fervent abolitionist, and a conductor on the Underground Railroad, and was a dear friend of Frederick Douglas. Sam had never known anyone like the Langdons; through them he met religious liberals, socialists, principled atheists, activists for women’s rights and equality, including the likes of Harriet Beecher Stowe, utopian socialist William Dean Howells, and British superstar author Charles Dickens. But it was Charles Langdon’s twenty-two year old sister, Olivia, to whom Sam was drawn to the most.

Olivia was a highly religious and serious minded young woman who suffered from frailty brought on by childhood and adolescent illness, and Sam was smitten with her from the first sight of her photograph that Charles showed him on their way back across the Atlantic. Upon meeting her, he was smitten, a shortly after wrote,

“Livy is the best girl in all the world and the most sensible. She is the sweetest and gentlest and daintiest and the most modest and unpretentious and the wisest in all things she should be wise in and most ignorant in all matters it would not grace her to know.”

She turned down his first proposal of marriage which came shortly after their meeting but she agreed to continue correspondence; he wrote her one hundred and eighty four letters over the next seventeen months, and eventually she fell in love with him and acquiesced to his proposal in November. Jervis had agreed, but only if Sam could supply him with letters of recommendation from acquaintances out west, where he had been a newspaper reporter and writer…

I think you might see where this is going.

Twain later wrote, half jokingly that his friends were less than helpful;

“They said with one accord that I got drunk oftener than was necessary and that I was wild and Godless, idle, lecherous, and a discontented and an unsettled rover, and they could not recommend any girl of high character and social position to marry me, but as I had already said all that about myself beforehand, there was nothing shocking or surprising about it to the family.”

Whether that was truly the case, or if it was Sam being Sam the yarn stretcher, who knows? Being that his brother had been a supporter of Lincoln and the first and only Secretary of the Nevada Territory possibly lent some gravitas, but regardless, Jervis Langdon grew to like Sam and the engagement was publicly announced in February of 1869 and the couple were married a year later.

In marriage, in order to please the woman he so deeply loved, Sam set about a life of personal reformation. While on the lecture circuit waiting for Innocents to be published, she sent him copies of Henry Beecher Ward’s weekly sermons which he claimed he read over and over again. He vowed to be a good Christian, to stop cussing, to give up drinking of alcohol even in social settings (that didn’t seem to last too long, she agreed to allow it as long as it was in temperance), and he cut back his use of tobacco considerably.

There it is— That’s why he never told the origin story as it related to his drinking days in Virginia City; it would have been a public embarrassment to his beloved bride and in-laws for him to acknowledge that he had once been a heavy drinking newspaperman along the mud and manure filled streets of a bawdy western mining town. It’s not that they didn’t know of his history, it’s just probable that they would rather not be reminded of it, or have it publicly become a rousing repeated legend about a member of their well mannered family.

Later in life, Clemens claimed not to have had a large experience in matters of alcohol when he was younger, but according to Mackay, the men who drank with him in The Old Corner Saloon remembered substantial quantities of chalk ground down to a nub behind the bar on his behalf. Sam and Mackay remained friends until Mackay’s death in 1902, Twain always cultivated the company of the well-to-do that he liked during the Gilded Age (a term that he first coined), especially those who had come up from nothing to make their fortunes among the well-heeled, and Mackay admitted to being “addicted to the society of literary men” (probably, like all Irishmen, in his heart he wished to be a man of letters himself). It seems Twain was well aware of the Mackay version of the story being told in smoke filled parlors where men had drinks and discussed business, as well as bit of joshing each other, yet it seems Sam never denied the alternate version of the name’s genesis. If he had ever publicly acknowledged it, even to disavow it, might have brought shame upon his beloved Olivia, and he would have never done anything that might risk breaking her heart.

To me, knowing what I know of ‘Sam the Man’ rather than ‘Mark Twain the Idol,’ the two chalk marks on the wall rings true; now, of course, Sam took to the calling out “Mark Twain” when ordering whiskey as recollection from his time on the boats, but once the boys at The Old Corner Saloon started to refer to him by his signature shout, I’m sure the bell rang in his head; “Hey, that’d be a fine nom de plume.” And yes, it was, and still is. It fits.

And by extension the truthfulness of his never wanting to do anything to harm the feelings of his only true love in this world is just another extension of his felicity and fidelity to her; he loved her so much, which in part explains why he was so broken when she died in 1904, six years before his own passing with Haley’s Comet in 1910.

Origin stories are always interesting to me; how did this or that come about? It’s my background in history I suppose, and an inquisitive sense as strong as that of my sight, smell, or touch, I suspect. Since I started writing seriously, just before the Pandemic, friends have often asked of my origin story, “Where did Jude MacAllen-Tatman come from?”

“He’s always been here,” I’d say for a chuckle, then I usually would add something like “I’ve always wanted a nom de plume.” I have never elucidated all of my reasoning, because I didn’t know if anybody would really be interested. But, a few weeks back, when I was laid up in a bed in the hallway at Sligo University Hospital (because they had no rooms available) over in the Republic of Ireland, while fighting a very aggressive infection, like so many things inside my head, I felt like this shouldn’t go unsaid any longer.

Jude: is from St. Jude Thaddeus, The Patron Saint of Lost Causes, and the saint I chose as my personal patron with my confirmation into the Church of Rome; the name Jude was placed upon me during that sacrament. Now, while I have still held onto the name, and the saint, I am long lapsed from any religious devotions, although I do like the ritual of Mass, and I have gone to mass in Ireland on various occasions. But truth be told, I’m an apostate, still think of myself as a lost cause, as well as a pagan and a heathen, yet on the side of the Rebel Jesus, (read the Gospels!) and of course, Saint Jude Thaddeus.

MacAllen: This one takes a bit of imagination on the cusp of metaphysical philosophy. Allen is easy enough– the name my mother chose for me, spelled with double ‘L’s and the ‘e’ so I have had to correct people my entire life when misspelled, mostly because they are attuned to ‘Alan’ but there is a difference, although it is delicate. ‘Alan’ should be pronounced ‘Al-ǎn’, whereas my name, if pronounced correctly, is al-LYN, like the Welsh. It is a surname, from Ireland (and also the British Isles due to migration). There’s a huge peat bog in the middle of Ireland called the Bog of Allen. I will bet there are at least some bones of ancestors thrown in there.

Mac is the prefix in the Gaelic languages of Ireland and Scotland that means “Son of–” When I started this pursuit of developing my writing and poetry it was as if I had been reborn of my own experience. Essentially, when I was nearing the age of 60, perhaps a couple of years before, it dawned on me; I am not who I once was, (and when you reach this age, none of us are). I am a product of everything that I have learned over six decades, especially from my mistakes, of which there are many and in some cases I am grievously sorry, and for others, I just feel stupid. I can dwell on those decisions that I feel have held me back, and those that have hurt others, or my selfishness, or regrets. Or I could begin again, learn from myself how to be a better me. This line of thinking became especially clear during my bout with cancer and the follow up with chemotherapy– I was on the very edge of oblivion, ready to join the great expanse, yet for some reason I found my way back, and knew there was more to do.

In essence, I am born of myself; I am my own son. Hence, I am MacAllen.

Tatman: Tatman is the name of my father and grandfather, the men who raised me and had the greatest impact upon my formative life. It is also the name of my only brother, who is the last touchstone to all of everything I ever was.

Tatman is a unique surname with a checkered and little known history. It's primarily of English origin, although it can be found in Wales and Ireland, as well as scattered all over America from New England to Oregon, in small pockets, usually of extended family groups like what we have in Ralls County. The name is derived from the Old English term 'tættec', meaning 'rag', and 'man'. So, the name Tatman essentially translates to 'ragman' indicating that the original bearers of this name likely went around begging for rags they could sell to others, or shred down into threads.

My father and grandfather were union Ironworkers; that's a great leap from being a ragman. I was always in awe of my dad and grandpa. The things they could do amazed me; I was never inclined with a mechanical sense of doings like they were, or that like my brother inherited.

I admire the men who came before me who carried that name.

I’m proud of the name Tatman. It reflects my roots, where I grew up and the people who came before me.

Regarding my brief illness in Ireland, (if you were wondering) I’m good now– the nurses and doctors in Sligo took GREAT care of me; over 36 hours they pumped me full of intravenous antibiotic, anti-inflammatories, and pain meds, patched me up and sent me on my way with prescriptions for oral meds, while under the watchful eyes of a retired RN (Marilee), and an MD and DO who were in our group of 12, and I spent most of the rest of the trip resting in hotel rooms, or as zombie on the Mercedes Sprinter coach. The whole trip now seems as if it were a vaguely lucid dream that I dozed in and out of, probably because of the fever and then the pain meds, but it wasn’t from the Guinness or whiskey; I’ve laid off the drink, and have been while I still mend from this infection. (Okay, I had a glass of wine or two on our last night in Dublin, and I’ve had a total of four drinks in the four weeks- maybe a couple more- since we’ve been home, but who’s counting?)

Before I wrap these ramblings up, one more thing regarding Sam Clemens:

I was talking to Dr. Albertini in his office one day, about Hannibal and Twain, when he told me this anecdote, which may be apocryphal, as I have looked for some verification of its validity online over the years and have found nothing. Regardless, as far as I’m concerned, it’s a great little story.

While giving a talk in Calcutta, India to British colonials, Twain told the privileged audience,

“All of the me, that’s still in me, is in a sleepy river town that lies halfway around the world.”

Sam, I feel what you meant.

Jude MacAllen-Tatman.

It reflects my past, my present, and what’s left of my future.

But you, my friends— you may call me by the name my mother called me-

-allen

* * *

JMcAT